(Un)reasonable adjustments? - difficulty in accessing reasonable adjustments for mental ill health

In the past, medics experiencing mental ill health have often encountered difficulties in accessing 'reasonable adjustments' to their work or study.

Dr Louise Freeman, co-chair of DSN, discusses whether there are any signs of improvement to the situation.

A summary version of this blog has been published on the British Medical Association website hereas part of a focus on access and invisible disability for UK Disability History Month 2020.

'Once reasonable adjustments are advised, it's normally straightforwards' - from a recent medical meeting on medics with disabilities and getting back to or staying in work.

That wasn't my experience. I encountered difficulty in agreeing suitable adjustments to my work in returning to my consultant role after sick leave with a bereavement reaction. I was asked by my employer 'What did you say to occupational health that they made this recommendation? ' regarding initial advice that night-time on-call should be avoided for the first three months of my return. This exchange developed into a lengthy and acrimonious discussion with predictable effects on my mental health. I was initially advised that the recommended adjustments would not fall within the remit of the (then applicable) Disability Discrimination Act 1995 or DDA - when returning to work after ten months off with a mental health diagnosis. The return to work process eventually resulted in my contract being terminated. At the time, I felt as if my symptoms were dismissed and seen as being 'self-reported' due to mental illness being an 'invisible' disability.

Was it just me?

Medics replying to the recent BMA disability survey echoed my own experience in that respondents reported difficulty in having recommended 'reasonable adjustments' implemented.

What are reasonable adjustments?

Medics experiencing mental ill health may find themselves considered to be a 'disabled person' under the Equality Act 2010 (which superceded the DDA) if their mental illness (considered as if without treatment) has a substantial negative long-term effect on their ability to undertake normal day to day activities. There is no requirement for the disability to be consequent to a medical diagnosis although some conditions such as addiction are specifically excluded from the Act. The definition still applies if you would have met the definition of disabled in the past and have now recovered. Subsequent reasonable adjustments - to remove substantial disadvantages to their work or study that a disabled person would otherwise experience - may be recommended by an occupational health specialist.

There is no over-arching legal definition of what is considered 'reasonable' regarding adjustments to a specific work or study environment as there is wide variation in employers' resources to consider changes and they are not obliged to follow recommendations.

Rethink Mental Illness provides examples of reasonable adjustments for mental health disabilities including changes to working hours or allowing time off for treatment, assessment or rehabilitation. [FR1]

Any improvements in 2020?

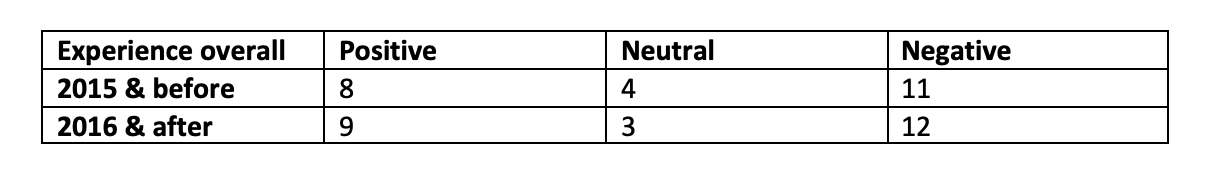

My own experience took place a decade ago - surely medics' recent experiences would be better? I asked over seven hundred DSN members of about their experiences of needing reasonable adjustments to their work or study due to mental ill health. Survey respondents were asked basic career information and to categorise their experience of reasonable adjustments as positive, neutral or negative with an option to comment with more detail if they wished. (The online survey was anonymous and confidential - with no identifying information collected.) I divided their anonymous responses into 2015 and before or 2016 and after to see if there was any change in recent years.

From the figures above, the more recent experiences may be marginally better but not markedly so. N.B. Four of the respondents from 2015 and before volunteered that they had lost their jobs as a result of their mental ill health.

Demographics for the survey respondents included a full range of ages and seniority varying from medical student to career grades from a wide variety of specialities. We might expect either junior doctors to have more difficulty in accessing reasonable adjustments or, conversely senior, career grade doctors to be more susceptible to the willingness of a single employer to make changes. However, in this small survey, there was no apparent correlation between career stage, specificity or age ass to whether medics had a positive or negative experience of reasonable adjustments. Several respondents reported mixed experiences: positive in one work / study environment but negative in another.

Commonly recommended adjustments included:

- working less than full time (LTFT)

- not working on-call / night shifts

- reducing home visits

- reducing clinical sessions

- amending pattern of the working week.

Problems cited with implementing adjustments included:

- employers not understanding their duty to consider adjustments under the Equality Act 2010

- speciality return to work policy not followed

- occupational health dismissive of concerns due to the doctor coping at work to that point

- refusal to consider longer appointments

- being placed in a more stressful work situation (instead of less)

Anonymous comments from respondents:

- 'Reasonable adjustments are often seen by those in authority as a sign of weakness and inability to cope.'

- On occupational health 'They don't know what to offer mental illness.'

- On asking to reduce working hours 'my colleagues only agreed to me reducing my hours once they realised that I was under psychiatric care .' and 'I was told to get a job somewhere else .'

- On the impact of poorly handled adjustments ''I do not feel valued as a team member. I feel a burden and am compared to colleagues who are doing more than me. This can have a direct impact on my mental well-being.'

- On a positive experience '

Felt supported by team. Flexibility worked both ways - if able,I helped out when a need and had time off when needed. I was able to accommodate medical appointments around days off or at either end of shifts.'

- On why adjustments seem so difficult to achieve 'There was a lack of guidance to myself and the colleagues with whom I was working. Everyone is so busy and stressed themselves there perhaps isn't any slack in the system to allow support for a colleague who is in need of some.'

- On being offered a training post with appropriate reasonable adjustments in place 'I was really grateful that occupational health and the training scheme agreed that it was important to prioritise my health.'

(after a previous less positive experience)

- On how having LTFT training agreed is not necessarily the end of the matter 'LTFT is still quite a mixed bag, working better in certain speciality training programmes than others. Also translating LTFT/reasonable adjustments agreed “on paper” into something that works in reality can be a never-ending battle.'

- 'Things that I mentioned would be helpful were ignored. Basically, you either work in the full horror of conditions as junior doc, or you take time off. No middle ground.'

Why does this matter?

One would hope that healthcare might be eager to promote best practice in enabling skilled employees to stay at or return to work after mental ill health - unfortunately this is still not the experience of many medics as shown by the results of this small survey.

Pro-actively addressing any potential barriers to work for medics with mental health related disabilities makes obvious economic sense. When medical school costs £250,000 - with far more expenditure to train a doctor to career grade level - failure to address mental health related reasonable adjustments is not in the long-term interests of the National Health Service (NHS). In addition, there is no reason why suitable adjustments to work or study should not be considered before the Equality Act disability definition is met - requiring fewer resources rather than waiting to treat a more serious problem when the threshold is eventually reached.

Access to reasonable adjustments should not be a 'postcode' lottery dependent on the variable practices of local organisations. The stigma of having had a mental illness, as well as being seen as demanding or needy, can create further barriers for individual medics. By raising awareness, we can (as a profession) improve support and challenge organisations to do better without relying on individuals to effectively advocate their own adjustments, often at a time when they feel particularly vulnerable during recovery.

I hope that the spotlight on healthcare professionals' mental health and wellbeing during the pandemic will result in substantial improvement in how we support each other in returning to work after mental ill health.

N.B. I completely accept that doctors with physical health issues (as well as other health professionals / other NHS employees) can often struggle to access reasonable adjustments. This article focuses on medics experiencing mental ill health because this area is DSN's specific charitable remit.